|

|

An Artwork as Means of Political Communication: The Peterloo era symbolism in Wilkie’s Chelsea Pensioners

Receiving the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday June 22d, 1815, announcing the Battle of Waterloo!!!  Figure 1. David Wilkie, Chelsea Pensioners Receiving the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday June 22d, 1815, announcing the Battle of Waterloo!!! 1818-1822. Oil on canvas, 97 x 158 cm. Wellington Museum, Apsley House, London. Picture credit: Tate Gallery, London.

In 1891, Russian artist Ilya Repin completed his monumental painting,

Zaporozhian Cossacks Writing the Letter to the Turkish Sultan. He envisioned this artwork as a celebration of Freedom,

representing Liberty, Equality and Fraternity.[1] He began to work on this composition in 1878 after returning to Russia after three years of extensive

study of Western art. The main composition of this picture refers to Wilkie’s Chelsea Pensioners Receiving

the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday June 22d, 1815, announcing the Battle of Waterloo!!! (Fig.1). Repin saw

the paintings of David Wilkie during his visit to London in 1876. On Repin’s priority-list preparing for the London

visit, Wilkie is listed as the second after Rembrandt.[2] In Repin’s picture, the veteran-warriors react to the Turkish ultimatum by amusing themselves

during the writing of a satirical response (Fig.2), while in Wilkie’s painting, the army veterans are amusing and cheerful

as a reaction to the reading of the gazette which contains a vivid description of the bloody battle (Fig.3). While the majority

of critics see Wilkie’s Chelsea Pensioners as the celebration of British victory, the Russian artist apparently

understood the composition of Chelsea Pensioners as a celebration of Freedom as an inner spiritual value which can

not be subdued by violence, restrictive laws or ultimatums. Wilkie’s picture also contains several metaphorical and

symbolic devises indicating the unrest and repressions of the era in which this artwork was created, thus connecting the subject

matter with the contemporary political situation. In 1820, when asked for his political opinion, David Wilkie refused to respond

arguing that “it’s being unsafe to give any opinion upon such a question in these times.”[3] However, the Chelsea Pensioners Receiving

the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday June 22d, 1815, announcing the Battle of Waterloo!!! is his political statement

suggesting that the new “most repressive laws Great Britain had known for generations” can not subdue the spirit

of freedom.[4] There are indications that the contemporary public understood this message. Therefore, the presentation

of Chelsea Pensioners in the Academy exhibition of 1822 can be seen as a form of political demonstration and communication. Figure 2. Ilya Repin, Zaporozhian Cossacks Writing the Letter to the Turkish Sultan. [Detail]. 1878-1891. Oil on canvas, 203 x 358 cm. State Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg. Picture credit: Cossacs.ca. http//www.cossacks/letter-to-sultan.htm.

The genesis history of Chelsea pensioners is extensively documented by Allan Cunningham.[5] Despite Duke Wellington’s request to paint the Chelsea pensioners in 1816, David Wilkie did not start preparatory sketches until 1818. On March 7, 1819, Duke Wellington suggested “to have in the picture more of the soldiers of the present day” and asked for the new sketches.[6] During their third meeting, on July 12, 1819, Wellington was satisfied with the sketches and authorized Wilkie to immediately begin with the execution of the final version on the canvas.[7] Remarkably, Wilkie did not start to paint until April of the next year. Studying for the picture, Wilkie conducted almost daily walks from his home at Kensington Gardens to Chelsea, observing and sketching the scenery and people:

Nor had he seen without emotions, as I have heard him say, the married soldier when they returned from the dreadful wars; sometimes two legs, as he observed, to three men, accompanied by women, most of them had seen, and some had shared in, the perils and hardships of the Spanish campaign, or had witnessed the more dreadful Waterloo.[8]

Figure 4. George Cruikshank, A free born Englishman! The admiration of the world!!! And the envy of surrounding nations!!!!! 1819. Hand-colored lithography on paper, 333 x 229 mm. British Museum, London. Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum.

During these walks to Chelsea, David Wilkie also experienced the charged political atmosphere. The early 1820s was a short, but very distinctive period of British history in which English political culture was dominated by the satirical prints- the visual signs. It was a consequence of the new restrictive laws known as the ‘Six Acts’ introduced on December 30, 1819, as a reaction to the massacre at Peter’s Square in Manchester. These new laws prohibited not just any kind of political meetings and gatherings of over fifty people, but also reduced the freedom of speech; the printed media was fined for any commentaries added to news (Fig.4). Since 1819, the political literature ceased to exist or went underground.[9] The satirical prints became the main form of political expression. The satirical prints were published in newspapers and magazines, sold at pamphlet-selling stores and exhibited in the windows of pubs and cafes. As John Gardner noted, “one could not traverse the London streets without being visually assaulted by prints, placards, illuminated transparencies, pamphlets, toys, broadsides, and every kind of cheap publications.”[10] Therefore, the public opinion was widely built on the visual media.[11]

In 1821, Wilkie made several changes to the Chelsea Pensioners, completing it in April 1822, just in time for the Summer Exhibition, which opened to the public on May sixth.[12] However, on May third, Wilkie went to the Royal Academy to make a few last changes to the picture which was already hanging on the wall.[13] The final title of the completed artwork was not suggested by the patron of this painting, Duke Wellington, it was provided by David Wilkie. There are two widely known artworks created in this era, which titles end with three exclamation marks, Cruikshank’s political print The Massacre at St. Peter’s Field or “The Britons Strike Home”!!! and three years later completed Wilkie’s painting Chelsea Pensioners Receiving the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday June 22d, 1815, announcing the Battle of Waterloo!!! The semantic and logical correlation of these two long titles may be a possible hint of their connection: George Cruikshank’s prints were widely published and distributed. They belonged to the English visual pop-culture of the 1810s-20s.

Figure 5. George Cruikshank, Massacre at St Peter’s or “Britons strike Home”!!! 1819. Hand-colored etching on paper, 245 x 344 mm. British Museum, London. Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum.

The consideration of the political situation as well as the influence of the popular political prints on the public opinion of this period are necessary in order to understand the social and political climate in which Wilkie created his Chelsea Pensioners. Cruikshank’s print The Massacre at St. Peter’s Field or “The Britons Strike Home”!!! is dated August 16, 1819, the same day as the massacre took place (Fig. 5). It shows the cavalry crashing with their sables the skulls of peaceful people, mostly women and children. It depicts the event when Manchester militia and British army attacked the peaceful meeting of over fifty thousand Manchester laborers demonstrating for their voting rights and better work conditions. It was also the first political event during which the feminist reform groups went with their own distinctive banners and color.[14] Eighteen demonstrators were killed, including women and children, over 400 people were wounded. Frederick Artz describes the public reaction as a “howl of anger and disgust … throughout the length and breadth of England”[15] The mass media defined this event as “Peterloo” an ironical reference to Waterloo. On October 1, 1819, appeared the print Peterloo Massacre by Richard Carlile (Fig. 6). The long title of this hand colored plate is a description of the event suggesting that it had to function as a key to the subject matter. During the early 1820s, George Cruikshank created several additional prints dedicated to this massacre. The Peterloo investigations, hearings of witnesses and trials went on until 1821. The government made the organizers of the meeting responsible, and for the first time in British history, the authorities conducted prosecutions for combined charges of unlawful assembly, conspiracy and riot.[16]

Figure 6. To Henry Hunt, Esq., as chairman of the emeeting assembled in St. Peter's Field, Manchester, sixteenth day of August, 1819, and to the female Reformers of Manchester and the adjacent towns who were exposed to and suffered from the wanton and fiendish attack made on them by that brutal armed force, the Manchester and Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry, this plate is dedicated by their fellow labourer, Richard Carlile: a coloured engraving that depicts the Peterloo Massacre (military suppression of a demonstration in Manchester, England by cavalry charge on August 16, 1819 with loss of life) in Manchester, England.

On February 23, 1820, as a reaction to Peterloo and curbing civil freedoms, the Spencean Philanthropic Society tried to assassinate the entire cabinet of the British government. The conspirators were found guilty of high treason on April twenty-eighth, and executed on May 1, 1820. In the same year, during the Queen Caroline Crisis, the majority of the population supported the banished Queen against the King and his government. After her death in August 1821, London’s crowds clashed with the troops escorting the coffin of Queen Caroline and forced them to take the procession through the streets of London instead of the planned inconspicuous transport out of the city. Two Londoners died and several were wounded during the clash with escorting soldiers. The public opinion was clearly against the government.[17]

Wilkie painted army veterans and their families as he observed them in 1820-21, reflecting the turbulent revolutionary atmosphere of these years. By rendering his subject matter, Wilkie also paid tribute to the visual culture and sensitivities connected with the recent political events. One of the reasons why this artwork had such strong emotional impact on the contemporary viewers is the fact that he placed the portrayal of the contemporary veterans seven years back, into the event which already became historical past, thus juxtaposing the eras of Waterloo and Peterloo.

David Wilkie was one of the most popular artists of the 1810s-1820s: several of his exhibited artworks had tremendous success by the public. He was beloved and celebrated for his humorous genre pictures resembling Dutch genre art of the seventeenth century. Therefore, the rumors that he was working on the Waterloo painting were widely circulating since 1816. However, the majority of the public, except for a few who visited his studio, had no idea regarding the concept developed by the patron of the picture, Duke Wellington in cooperation with the artist to represent the army veterans at the Chelsea hospital.[18] Only the pensioners, sketched at the Chelsea Hospital expected to recognize themselves in the picture. Therefore, the public anticipated to see Wilkie’s picture primarily as the memorial of the Waterloo victory. Since the opening of the exhibition, the room in which Chelsea Pensioners was exhibited was overcrowded. The observers estimated that approximately four hundred people were regularly present in the room trying to get a glimpse at the picture. Therefore, Wilkie had to order the rail to protect his painting from accidental damages. Over 90, 000 people came to see this painting and statistically, this exhibition was one of the most visited in the history of the Royal Academy, and this was credited to the success of Wilkie’s artwork.[19]

Richard Altick describes how the artistic novelty, the representation of the army veterans and other people belonging to the low classes of British society resulted in the democratization of the art exhibition, “attracted by the subject, men and women representing all but the lowest works of life, including the very classes whom the shilling admission charge had originally been designed to exclude, crowded Somerset House day after day.”[20] Cunningham noted that “the battle of Waterloo itself made scarcely a greater stir…than did The Reading of the Gazette, when it appeared in the Academy Exhibition.”[21] The old crippled veterans and younger Waterloo heroes, living with their families on shilling-and-ten pence a day pensions for their service for the country, saw themselves celebrated and honored in Wilkie’s painting. The viewers also understood the symbolical character of this representation. It was pointed out that the soldiers of Waterloo, shown in the painting, could not be in London in June 1815, four days after the battle.[22] However, it is not known how the patron of this painting, Duke of Wellington, the celebrated army leader at the Waterloo battle, Parliament member and Tory politician, member of the party responsible for the restrictive laws, perceived Wilkie’s final concept. He did not see the completed artwork until the exhibition. After the exhibition, the painting went directly to Apsley House, Wellington’s residence, and it was not available for public viewing until 1853. Motivated by the enormous public success of this picture, Wilkie requested an unusually high price of 1,200 guineas, which Wellington paid without any protesting. However, in 1831, John Burnet created an engraved copy of Chelsea Pensioners. The reviews regarding the publication of this print praised Wilkie’s picture as “a fine remembrancer of a glorious victory.”[23] By 1831, the era of Peterloo and restrictive laws became historical past and the political visual symbolism of that period lost its charged revolutionary meaning.

The contemporary viewers were impressed by the precision with which David Wilkie rendered the location of his Chelsea Pensioners. It is the King’s Road leading from Pimlico Road to the Northern Gate of the Chelsea Hospital. On the left side of the picture plane is the hospital’s stone wall with the Northern Gate in the background. Behind the wall is the exactly rendered Chelsea Hospital. On the right side of the picture plane is a row of also precisely drawn Chelsea houses. The veterans are gathering outside of the Duke of York public house around the table which is placed in the middle of the road, thus blocking the way from Pimlico to Chelsea Hospital. Wilkie painted sixty figures crowded together on the street, which may point to the new law, the “Seditious Meeting Act”, which was introduced on December 30, 1819 prohibiting any “meeting of any description of persons exceeding the number of fifty persons…”[24] Wilkie’s ‘unlawful meeting’ of the pensioners demonstrates the absurdity of this new law.

Figure 7. David Wilkie, Chelsea Pensioners Receiving the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday June 22d, 1815, announcing the Battle of Waterloo!!! Applied compositional lines. Picture credit: Vadim Moroz

Chelsea Pensioners is a St. Andrew cross composition (Fig.7). Wilkie used this compositional devise in several of his paintings. For example, Blind Man’s Buff and The Penny Wedding are also based on such St. Andrew cross composition. However, he camouflaged compositional lines by moving the composition slightly off center and placing some figures and elements in such a way that they break clearly defined geometrical construction. The composition of Chelsea Pensioners has an organizational function pointing to the center, in which the Chelsea in-pensioner eating oysters is located. His head is turned three-quarter to the veteran reading the gazette. There is a smile on his face; the mouth is slightly open, as if he is in process of making a comment. His right hand holds the dish with the oysters, the fork with an oyster on it is in his left hand. The exhibition viewers as well as the contemporary critics questioned the meaning of the oysters in this painting. The reviewer for The European Magazine noted that Hogarth also painted oyster eating “glutton” in his Elections picture, but it is difficult to recognize any connection, therefore he concluded, “we are at loss to guess why Wilkie chose oysters for a principal feature in his painting.”[25] The reviewer for the New Monthly Magazine was amused observing how “one enthusiastic and high-minded critic has stept forward to observe that Wilkie committed an important anachronism by painting oysters in June.”[26] However, it is hard to believe that the contemporary observers did not associate the oysters with Shakespeare’s “…then the world’s mine oyster, which I with sword will open.”[27] This phrase suggests the usage of violence in reaching worldly goods. The connection of such idea with the low-class army veterans may appear as a revolutionary radical call. Discussion of such subject in the media was not possible according to the ‘Six Acts’; this may explain why the contemporary reviews were kept on the small talk level.[28] The oyster harvest was regulated by the acts of parliament and the Oyster Day, the first day of the oyster harvest on which they came to London’s markets was set for the late August.[29] Cunningham pointed that David Wilkie was pleased by such public reactions as “to eat oysters in June was contrary to act of parliament, though not contrary to nature, whose word to them was, kill and eat.”[30] Thus, the metaphorical meaning of oysters became a quintessence of Wilkie’s main message of this painting- the striving to natural freedom which can not be subdued by the restrictive law.

The veteran in Wolfe uniform reading the gazette is located left of the pensioner eating oysters. He is the psychological center of the composition providing the logical story context: most of the figures are facing him or listening to his reading. The young mother standing behind him and starring into the gazette is noted by several critics as one of the most emotional figures in the composition. Her face, especially her eyes, was the reason, why French artist Theodore Gericault by observing the painting in Wilkie’s studio was not able to hold back his tears.[31] However, most of the figures in the composition appear to be in good mood, to cheer or celebrate. It may leave an erroneous impression that the London Gazette Extraordinary may contain a euphoric cheerful report of the glorious victory. This is not the case. This particular gazette consisting of four pages contains almost a three-page long Wellington’s dispatch which describes the dreadful battle and one page with the names of the killed and wounded officers. Regarding the victory, Wellington wrote, “…such a desperate action could not be fought, and such advantages could not be gained, without great loss; and I am sorry to add, that ours has been immense.”[32] The added list of killed and wounded British officers, including eleven generals and thirty-two colonels, was a vivid illustration of the bloody massacre described in the dispatch.

The reading of the London Gazette on June 22, 1815, was indeed a historical event, but there was not much joyful, loud celebration. Thackeray remembered, “Who can tell the dread with which that catalogue was opened and read!...the great news coming of the battles in Flanders, and the feeling of exultation and gratitude, bereavement and sickening dismay when the list of the regimental losses were gone through.”[33] On June 22, 1815, the war was still going on and the final victory as the consequence of this battle came weeks later. The pensioners in Wilkie’s painting are not shaken by the dreadful description of fighting and death. As the war veterans, they show their bravery and inner strength: such people can not be subdued by the dreadful violence. In connection with the symbolism of “world’s mine oyster,” this rendering represents Wilkie’s position to the unrest and violence of these years: he is on the side of the veterans, struggling low classes of British society.

Figure 8. David Wilkie, Untitled sketch, c.1819-1821. Brown ink on paper, 110 x 179 mm. British Museum, London. Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 9. David Wilkie, Untitled sketch, c. 1819-1821. Brown ink on paper, 50 x 63 mm. British Museum, London. Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 10. David Wilkie, Untitled sketch. c.1819-1821. Brown ink on paper, 106 x 178 mm. British Museum, London. Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum.

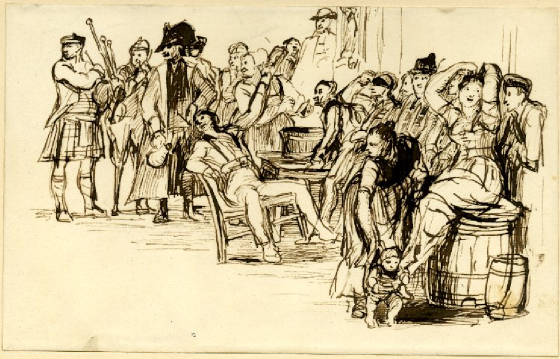

The comparison of preparatory sketches and final version reveals how the original concept as the genre scene was transformed into the final symbolic representation adjusted to the realities of the Peterloo era. For example, in the sketches, the group of women at the foreground was shown busy to prepare food and take care of playing children (Fig.8). There was an emotional exchange and interconnections between the figures. In the sketches, there was a remarkable emotional tenderness in the way the soldier was involved with the child (Fig.9 and 10). This concept is to the most part not present in the final execution. In the painting, the soldier is holding the toddler up away from his uniform. Both the soldier and the toddler are facing the gazette reading pensioner. There is no emotional interplay as it was present in the sketches. This emotional distance results in the ambiguous meaning of these figures. This ambiguous symbolism of the final version appears to reflect the public sensitivities. The symbolism of the satirical prints showing the soldiers killing innocent children was present in the public consciousness. The first death victim of the Peterloo massacre was a toddler, several women were killed and over hundred women wounded. Such pictures, depicting the Peterloo massacre were the part of the pop-culture of this period. It may be the reason why Wilkie reduced the emotional interconnection between the soldier and the toddler in the final version.

In the preparatory ink sketches, the highlander belonged to the main figures and was located in the right middle-foreground near the veteran with the wooden leg (Fig.8). In one of the sketches, he was even the father playing with a toddler (Fig 11). But in the final version, he is located on the background turning his back to the viewers. He is playing his bagpipe next to the Jewish dealer who is trying to convince a guard-on-foot soldier to buy something. This small group in the background is one of the last humoristic genre devises left in the final painting. This scene can be also seen as a metaphor. However, the Jewish dealer refers to the fact that the Jew’s Row begun just behind the King’s Road.

Figure 11. David Wilkie, Untitled sketch. c.1819-1821. Brown ink on paper, 86 x 70 mm. British Museum, London. Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum.

The original place of the highlander in the middle ground next to the veteran with the wooden leg took a woman waving a piece of cloth, probably her scarf. There should be a reason why this figure is more important then the highlander, who was moved to the background. It is remarkable that her scarf is white. White was a political color chosen by radical groups and Female reform societies to symbolize struggle for equality.[34] It was also shown in the wide distributed print by Richard Carlile that the feminist group members were dressed in white and had white banners during the Peterloo massacre.

In the late eighteenth century, English radical movement has chosen Jacobin green and white as revolutionary emblematic colors. In the early nineteenth century, green became stronger associate with Irish national movement, therefore, white color predominated the political symbolism of English radical revolutionaries.[35] The pacifist groups against the British involvement in Napoleonic wars also used symbolism of white color. Samuel Bamford describing Peterloo, stated, “I noticed not even one, who did not exhibit a white Sunday’s shirt, a neck cloth, and other apparel.”[36] After Peterloo, white was widely adapted as the color of the political struggle for equality.[37] Even later, in 1840s, white scarves symbolized radical political position.[38] Katrina Navickas pointed out that, “As Lynn Hunt identifies, emblematic clothing made “a political position manifest” and, in so doing, “made adherence, opposition, and indifference possible.”[39] Therefore, since December 30, 1819, the display of any politically emblematic color was prohibited by the Seditious Meeting Act.[40] In 1820s, wearing or waving any white scarf was a political statement.

At the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition of 1818, William Turner exhibited The Field of Waterloo, which shows the nightly landscape covered with the dead bodies. Such anti-war pictures were unsuitable for the commemoration of Britain’s greatest victory. The public needed a war memorial. David Wilkie apparently fulfilled such expectations. But he also expressed his political opinion to the contemporary situation using the pop-cultural symbolism of the era when this artwork was created. Later, the political and social situation as well as the visual language has changed and as result, the Peterloo era symbolism of the Chelsea Pensioners became hardly accessible. Today, this artwork is commonly understood as the Waterloo memorial and the celebration of “the common man, but only in a certain role, that of plucky patriot and model soldier.”[41] However, Wilkie’s vision that the persecutions and repressive laws will not be able to hinder the natural striving for freedom proved to be confirmed: the restrictive laws expired during the 1820s and hard-fought-for democratization reforms came finally in 1832.[42] Considering the overall impact of Wilkie’s artwork, it can be stated, that the presentation of Chelsea Pensioners at the 1822 Academy Summer Exhibition was the artist’s contribution to the liberalization of British society. Bibliography

Artz, Frederick. Reaction and Revolution 1814-1832. New York: Harper & Row, 1934. Black, Jeremy. A New History of England. 2nd revised edition. Gloucesterhire: History Press, 2008. Bloy, Marjie. “The Six Acts 1819” The Victorian Web. Literature, history and culture in the age of Victoria. http://www.victorianweb.org/history/riots/sixacts.html. (accessed Feb.6, 2012). Bush M.C. “The Women at Peterloo: The Impact of Female Reform on the Manchester Meeting of 16 August 1819.” Scholarly History Journal. Vol. 89, issue 294, [Apr. 2004]: 209-232. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004. Chandler, James. England in 1819. The Politics of Literary Culture and the Case of Romantic Historicism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998. Cunningham, Allan. The Life of Sir David Wilkie: with His Journals, Tours, and Critical Remarks of Arts, and a Selection from His Correspondence. 3 vols. London: John Murray, 1843. “Digressions in the Two Exhibition-Rooms.” The New Monthly Magazine. Vol. IV, No.XXI. [Sep.1, 1822]: 219-22. Boston: Oliver Everett, 1822. “Exhibition at Somerset House.” The European Magazine and London Review. Vol. 81-82. [May 1822]: 466. London: Philological Society, 1822. “Fine Arts Publications.” Ed. Richard Bentley. The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal. Vol. 33. [January 1, 1831]: 534. London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1831. Gardner, John. Poetry and Popular Protest: Peterloo, Cato Street and the Queen Caroline Controversy. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Gower, Ronald. Sir David Wilkie. London: George Bell, 1902. Hutchison, Sidney. The History of the Royal Academy 1768-1986. 2nd Ed. London: Robert Royce, 1986. Jackson, David. The Russian Vision. The Art of Ilya Repin. Schoten: BAI, 2006. Jones, Catherine. “Scott, Wilkie, and Romantic Art.” Ed. David Duff. Scotland, Ireland and Romantic Aesthetic. Cranbury: Associated University Press, 2010. Jones, Jonathan. “The Home Front.” Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2002/sep/26/art (accessed Feb. 17, 2012) Linch, Kevin. Britain and Wellington’s Army. Recruitment, Society and Traditions, 1807-15. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts, Science, &c. for the Year 1831. London: Literary Gazette Office, 1831. Lobban, Michael. “From Seditious Libel to Unlawful Assembly: Peterloo and the Changing Face of Political Crime c.1770 – 1820.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. Vol.10.No.3. [Autumn 1990]: 307-52. Oxford: University of Oxford Press, 1990. The London Gazette Extraordinary. No.17028, [Thursday, June 22, 1815]: 1213-16, 1815. McCord, Norman and Bill Purdue. British History 1815-1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. Mollett, John William. Sir David Wilkie. London: Sampson Law, 1881. Navickas, Katrina. “That sash will hang you”: Political Clothing and Adornment in England, 1780-1840.” Journal of British Studies. Vol. 49, No. 3, [July 2010]: 540-565. Chicago: University of Chicago Press on behalf of The North American Conference on British Studies, 2010. “Oyster-Day.” The London Saturday Journal. No.83, [Saturday, August 6, 1842]: 61-62, 1842. Patten, Robert. George Cruishank’s Life, Times, and Art. Vol.1. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992. Penny Cyclopedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Vol. 27. London: Charles Knight, 1843. Read, Donald. Peterloo the Massacre and its Background. Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 1958. “Royal Academy Exhibition.” The Athenaeum and Literary Chronicle. [June 10, 1829]: 662-63. London: Westley, 1829. Shakespeare. The Complete Illustrated Shakespeare. Ed. Howard Staunton. Reprint of The Plays of Shakespeare. London: Routledge, 1858-61. New York: Park Lane, 1979. Steegman, John. Victorian Taste. A Study of the Arts and Architecture from 1830 to 1870. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press, 1971. “Things you never knew about the Summer Exhibition.” Royal Academy of Arts. http://www.royalacademy.org.uk.Summerexhibitions/things-you-never-knew-about-the-summer-exhibitions/101/AR.html (accessed 26 Feb. 2012}. Tromans, Nickolas. David Wilkie The People’s Painter. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007. Tromans, Nickolas. David Wilkie Painter of Everyday Life. London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2002. Wilkie Gallery: The Late Sir David Wilkie, R.A. Including His Spanish and Oriental Sketches, with Notices Biographical and Critical. London: George Virtue, 1848. Winkenweder, Brian “The Newspaper as Nationalist Icon, or How to Paint ‘Imagined Communities.” Limina. A Journal of Historical and Cultural Studies. Vol.14, [2008]: 85-96. http://www.limina.arts.uwa.au/date/page/157411/Winkenweder.pdf.

[1] Repin. Letter to Stasov in David Jackson. The Russion Vision. The Art of Ilya Repin. (Schoten: BAI, 2006), 95 [2] David Jackson. The Russian Vision. The Art of Ilya Repin. (Schoten: BAI, 2006), 63 Wellington’s art collection including Chelsea Pensioners, became open to the public in 1853, see Apsley House. http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/daysout/properties/apsley-house/history-andresearch/history/3-open-to-the-public. [3] Letter to Miss Wilkie [25th Oct. 1820] in Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2, (London: John Murray, 1843), 46 [4] Frederick Artz. Reaction and Revolution. 1814-1832. (New York: Harper, 1934), 125. [5] See Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2, (London: John Murray, 1843) [6] Wilkie’s Diary in Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2. (London: John Murray, 1843), 17 [7] Wilkie’s Diary in Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2, 18 [8] Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2, (London: John Murray, 1843), 50 [9] James Chandler. England in 1819. The Politics of Literary Culture and the Case of Romantic Historicism. (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1998), 122 [10] Robert Paten. George Kruishank’s Life, Times, and Art. Vol.1 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1992), 172 [11] John Gardner. “Poetry and Popular Protest: Peterloo, Cato Street and the Queen Caroline Controversy” timeshighereducation (http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk) [12] “Exhibition at Somerset House.” The

European Magazine and London Review. Vol. 81-82. [May 1822]: 466. (London: Philological Society, 1822), 466. [13] Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2, (London: John Murray, 1843), 67 [14] M.C. Bush. “The Women at Peterloo: The Impact of Female Reform on the Manchester Meeting of 16 August 1819.” Scholarly History Journal. Vol. 89, issue 294 [Apr.2004]:209-232 (Manchester: Manchester Metropolitan University, 209-232). [15] Frederick Artz. Reaction and Revolution. 1814-1832. (New York: Harper, 1934), 125. [16] Michael Lobban. “From Seditious Libel to Unlawful Assembly: Peterloo and the Changing Face of Political Crime c. 1770-1820.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies. Vol.10.No.3, (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1990), 310. [17] Norman McCord. British History1815-1914.2nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 29. [18] See Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2, (London: John Murray, 1843). [19] Royal Academy of Arts. “Things you never knew about the Summer Exhibitions” (http://www.royalacademy.org.uk), access 16 Feb. 2012. [20] Richard Daniel Altick. The Shows of London. (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1978), 406 [21] Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2, (London: John Murray, 1843), 74. [22] Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2, (London: John Murray, 1843), 78. [23] “Five Arts Publications.” The New Monthly Magazine. Vol. 33 [1331, part III]:1831, (London : Colburn, 1831), 534. [24] “Seditious Meeting Bill” 60 Geo.III.Chap.6 in Parliamentary Debates. [Vol. XLI]: 23Nov.1819-28Feb.1820, (London: Hanzard, 1820), 1657-1658. [25] “Exhibition at Somerset House.” The European Magazine and London Review. Vol. 81-82. [May 1822]: 466. (London: Philological Society, 1822), 466. [26] “Digressions in the Two Exhibition-Rooms.”

The New Monthly Magazine. Vol. IV, No.XXI. [Sep.1, 1822]: 218-22. (Boston: Oliver Everett, 1822), 219. [27] Shakespeare. The Merry Wives of Windsor. Act II, Scene II. [28] “The Blasphemous and Seditious Libels Act (60 Geo III cap.4) and “The Newspaper Stamp Duties Act (Geo III, cap.9). Parliamentary Debates. [Vol. XLI]: 23Nov.1819-28Feb.1820, (London: Hanzard, 1820), 1647-1690. [29] “Oyster-Day.” The London Saturday Journal. No.83, [Saturday, August 6, 1842]: 61-62. [30] Allan Cunningham. The Life of Sir David Wilkie. Vol.2. (London: John Murray, 1843), 78. [31] Nickolas Tromans. David Wilkie The People’s

Painter. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University

Press, 2007), 142. [32] Duke Wellington. “The Dispatch to Earl Bathust. June 19, 1815.” The London Gazette Extraordinary. [Numb. 17028]: June 22, 1815. 1213-1215. [33] William Makepeace Thackeray. The Vanity Fair.

in Jonathan Jones. “The Home Front.” The Guardian. [26 Sep.2002] http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2002/sep/26/art.html. [34] Katrina Navickas. “That sash will hang you”:

Political Clothing and Adornment in England, 1780-1840.” Journal of British Studies. Vol. 49, No. 3, [July 2010]: 540-565. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press on behalf of The North American Conference on British Studies, 2010), 556 [35] Katrina Navickas. “That sash will hang you”:

Political Clothing and Adornment in England, 1780-1840.” Journal of British Studies. 553. England, 1780-1840.” 556. [37] Katrina Navickas. “That sash will hang you”:

Political Clothing and Adornment in England, 1780-1840.”

Journal of British Studies, 557. [38] Ibid.,553. [40] Ibid., 542. [41] Nickolas Tromans. David Wilkie Painter of Everyday

Life. (London: Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2002), 90. [42] Representation of the People Act 1832. Acts of Parliament, [2 &3 Will IV]: 1832 |

Figure 2

Figure 2  Figure 3 {detail of Fig.1}

Figure 3 {detail of Fig.1}